Gallery Collection

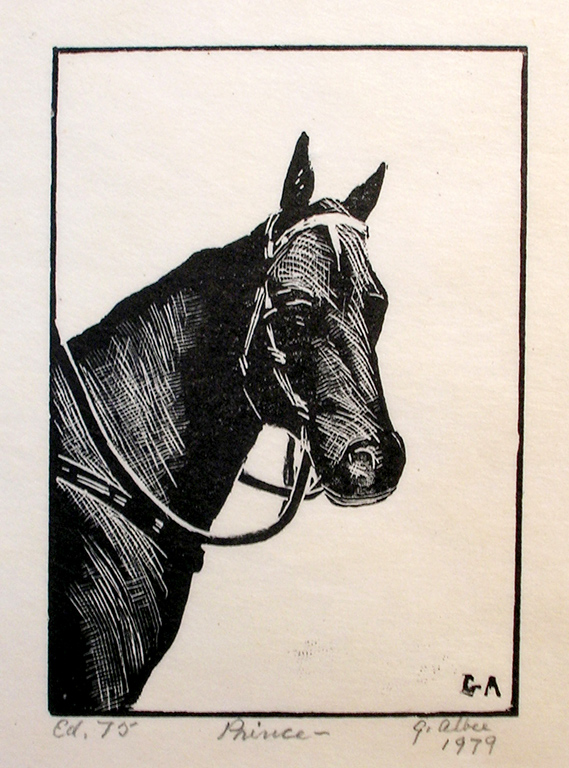

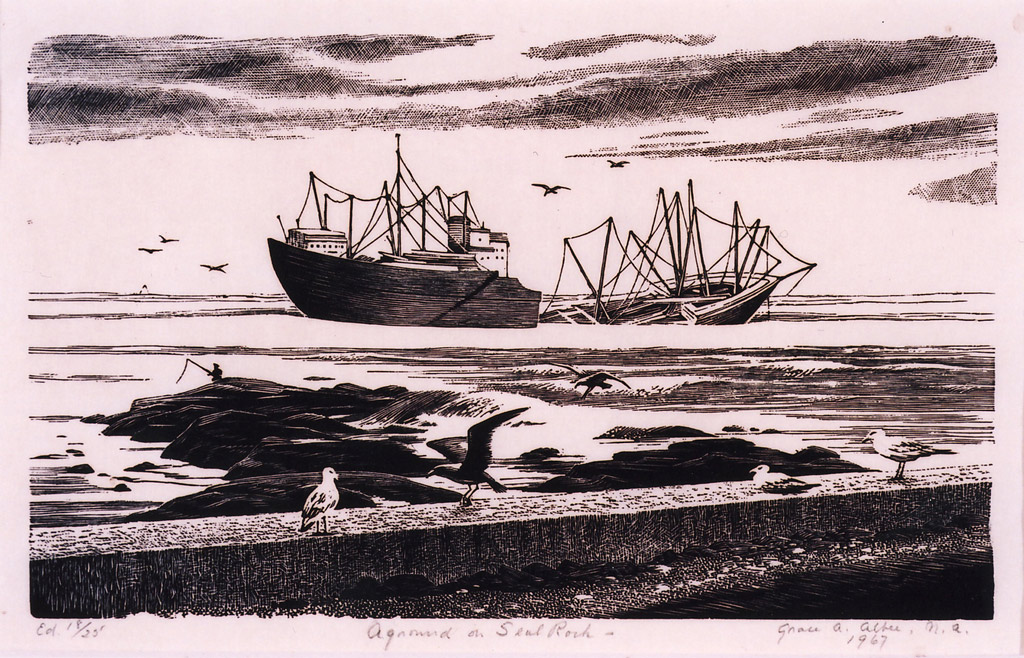

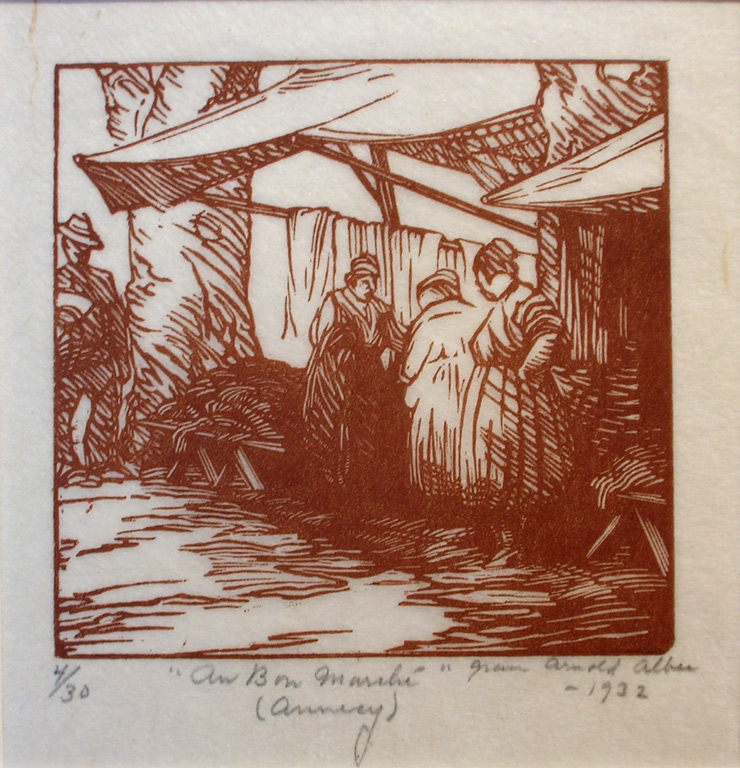

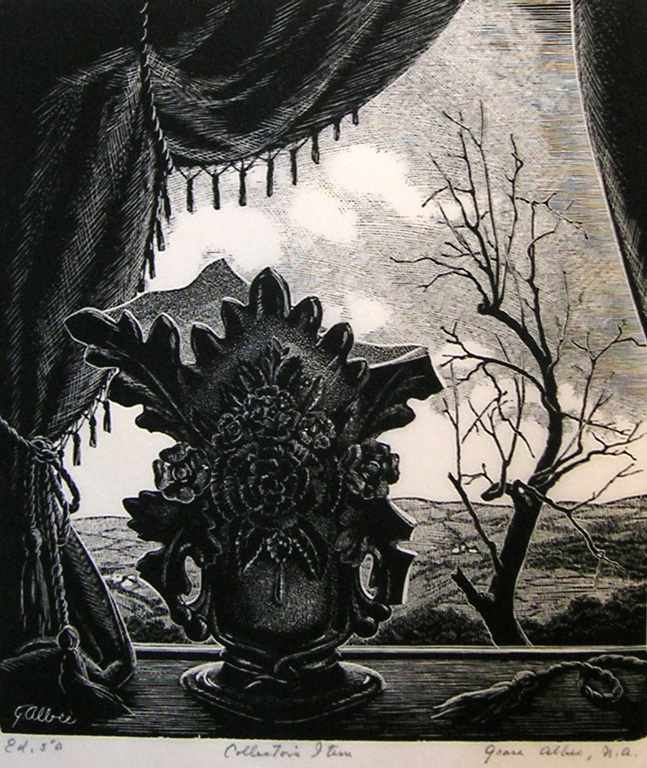

Grace Albee (1890-1985): Engraver

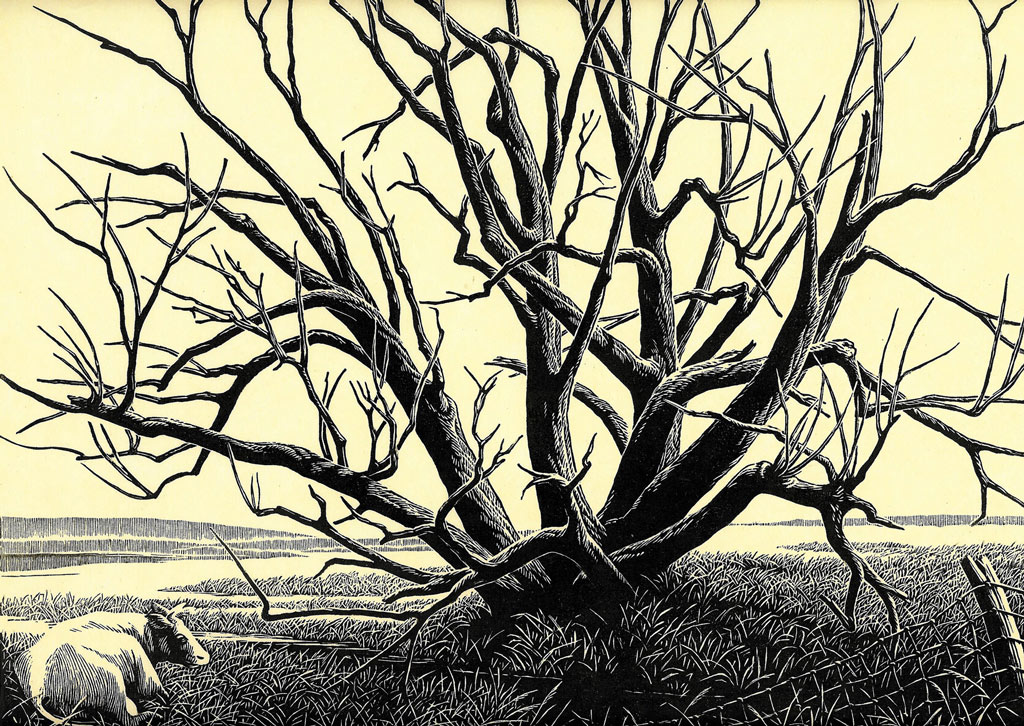

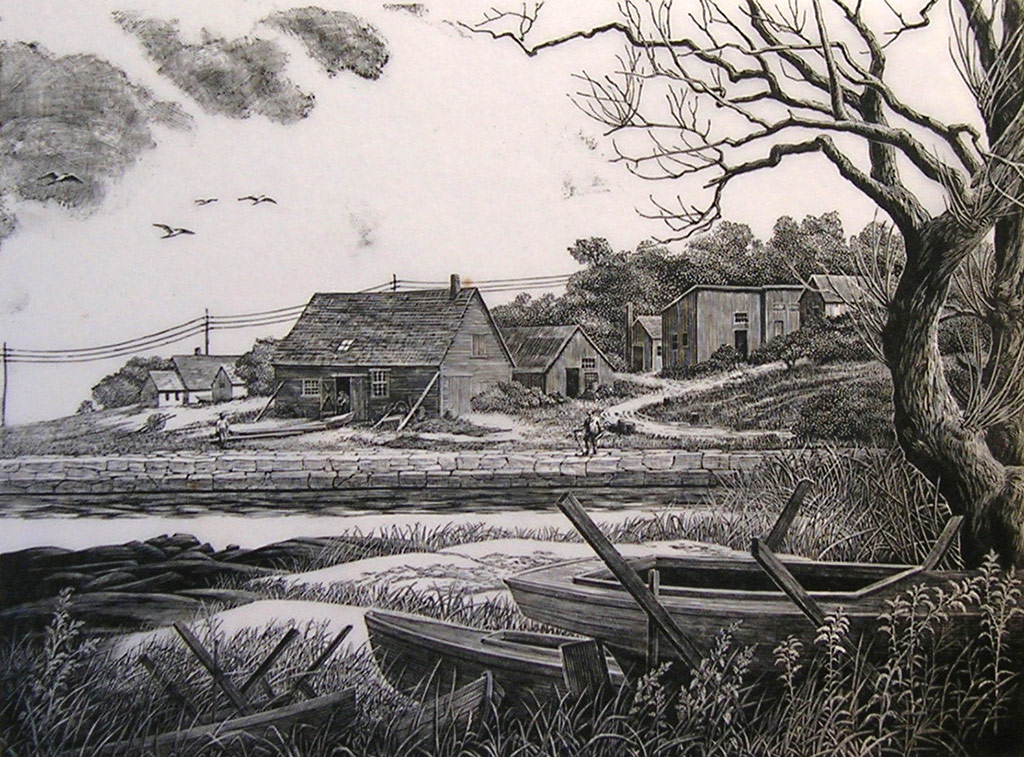

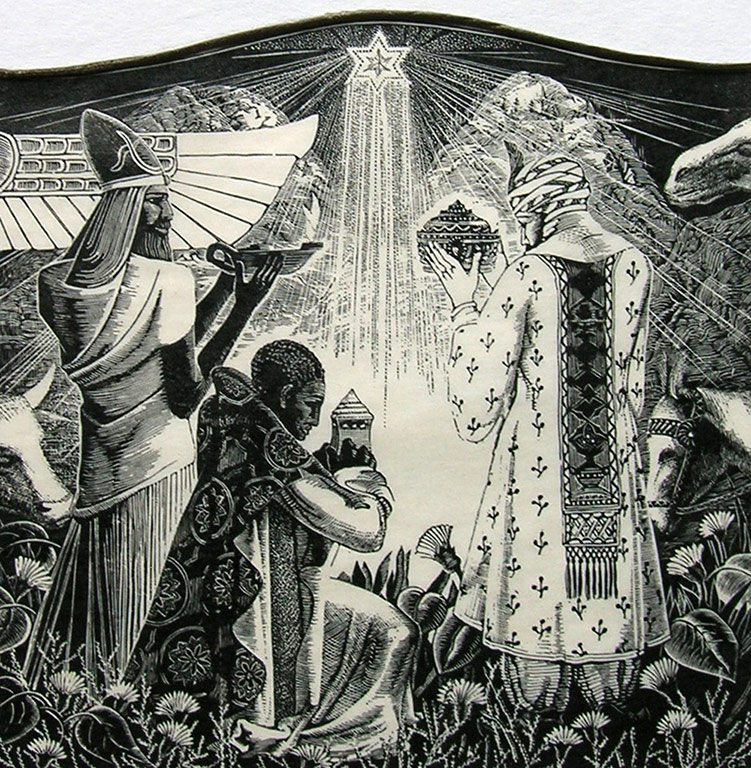

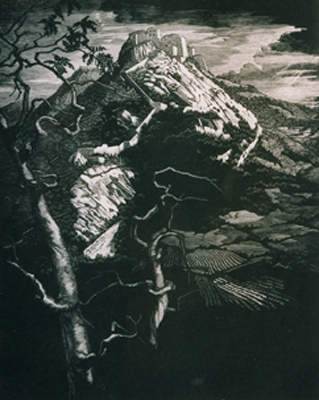

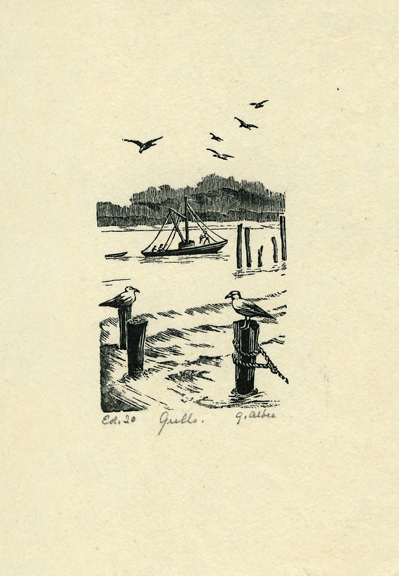

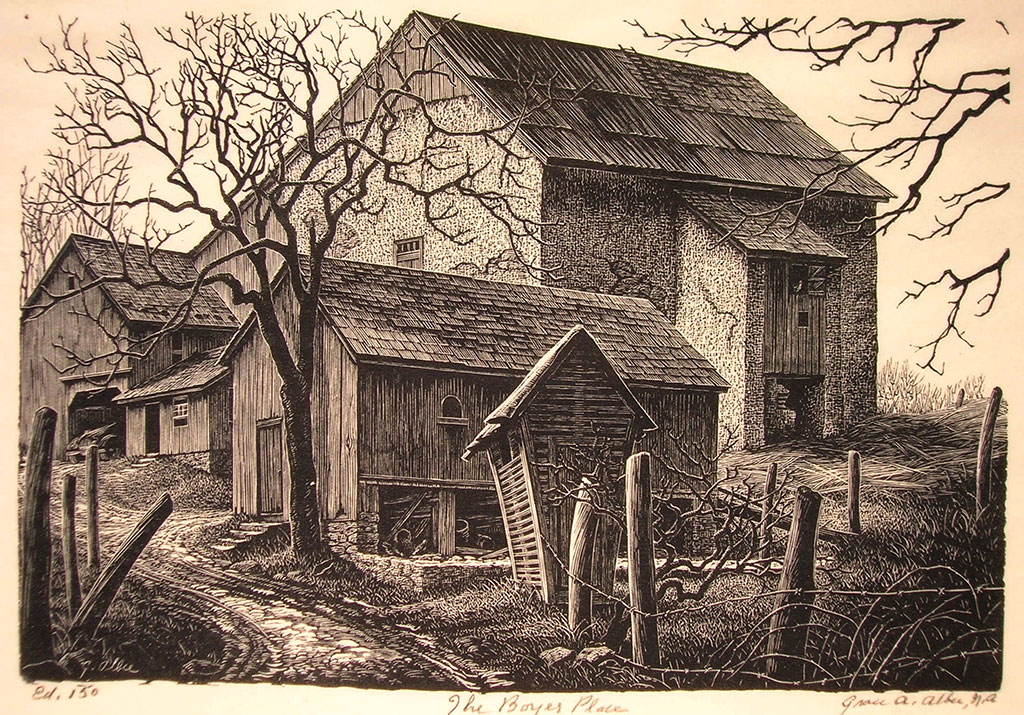

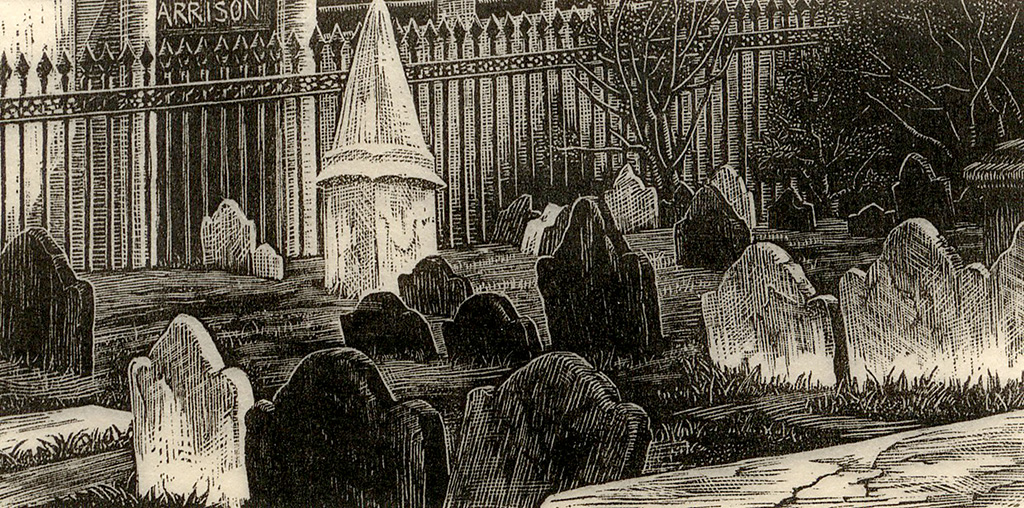

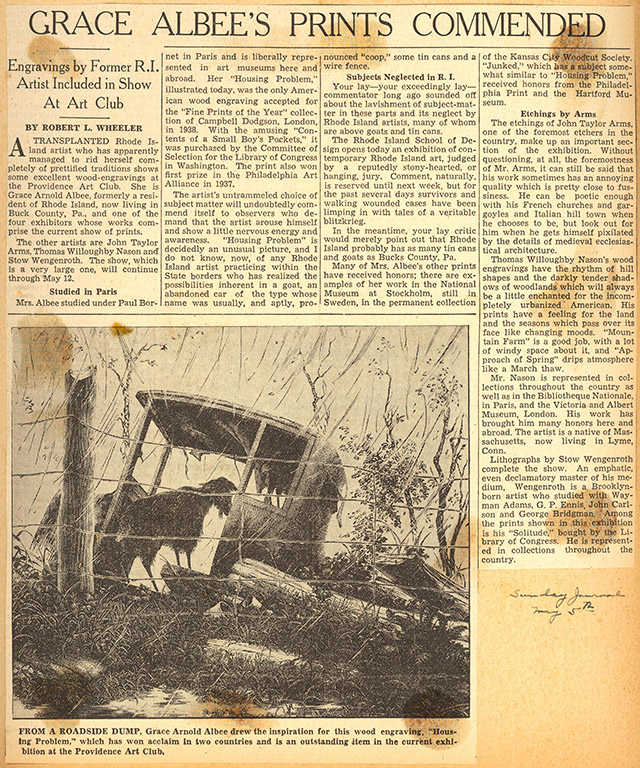

Grace Albee produced over two hundred prints in a fifty year career span as a wood engraver and became noted as a keen observer of the world around her, be it local scenery of Paris, Pennsylvania farm country, or the Rhode Island sea coast. Her velvety soft images narrate a story and belie the sometimes cold and distant engraving process. Albee’s oeuvres found collectors in the private and museum world, fitting in nicely with the Thirties and Forties regional realism that Thomas Hart Benton had popularized among American artistic onlookers.

Albee was first exposed to a wood engraving as a child when looking through her grandfather’s old books. A precise and exacting personality such as Grace’s was inclined toward this painstaking and meticulous medium. Despite her father’s disdain for the frivolous art world, the young woman attended Rhode Island School of Design and there met her artist husband, Percy, sealing her art destiny. It was in 1928 that the Albees departed Providence and enthusiastically made their way to the artistic mecca of Paris. With five boys to care for, the young mother managed to take her first and only lessons in wood engraving with Paul Bournet. From this point onward, Grace immersed herself in the wood engraving medium and would pursue no further instruction other than her own experimentation and self-tutelage. Skillfully rendered drawings using highly durable papers from the orient, Albee would hand print her images.

Back in the United States by 1938 and ten years into her career, with sixty-six images to her credit, Grace began to garner significant recognition in the way or awards and entry into museum collections. By the time she was accepted into the prestigious National Academy of Design, a reputation for artistic boldness, delicacy of detail, and clever handling of textures was established. Grace Albee became known for imagery not about humanity, but rather, the effects of human habitation in the country and city. There was humor but also poignant images in scenes of outhouses, escaping farm animals, and discarded artifacts from a time gone by. For fifty years she focused on her craft. An important commendation came with a 1972 Brooklyn Art Museum retrospective exhibition. Upon her death at the age of ninety-five, she had accumulated over fifty awards and was in thirty-three museum collections. For a woman who almost outlived her fame, these accomplishments served as a comforting tribute to her importance in the competitive field of printmaking.

View Slideshow

View Slideshow Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image Slideshow Image

Slideshow Image